What the Most Sordid Russian Gay Bar in Riga Taught Me About Identity Politics

Three Gay Prides ago, I was in Riga, Latvia. I’d been there a few times before to visit my Latvian grandparents, who’d bought an apartment there in 1991 after Latvia gained independence from the Soviet Union. They now spent their summers in Riga, known as the “Jewel of the Baltic.” On these trips, I had come to love the city’s Art Nouveau architecture and punky graffiti, the amber jewelry carts on every corner, the old women who sold plastic cups of chanterelles and wild strawberries at the central market, the white nights and the cold borscht and the beaches. But I was often distracted by plans of my own, plans that I could never reveal to my grandparents: to get to know the gay bars in Riga.

On one trip in 2007, I did a search on MySpace for “lesbians” in the area. I came across a feminist anarchist punk named Marina, who agreed to accompany me to one or all of the city’s gay bars—a bar called Purvs, meaning “swamp” in Latvian, advertised as a club for "gejiem, lesbietēm, biseksuāļiem, transvestītiem.” I visited another of the city’s gay bars, Golden, on the following trip.

After my grandparents died, I didn’t return to Riga until the summer of 2015, when VICE Magazine (print, RIP) enlisted me to report on EuroPride Riga 2015—the first time in the event’s 24-year history that it would take place in a post-Soviet nation. Latvia’s first LGBT Pride march in 2006 had been violently attacked by a mob armed with human feces and holy water, placing the country on Amnesty International’s Human Rights Watch list. Since then Latvia’s “embattled gay rights movement,” “desperate for support and visibility,” had worked tirelessly to bring EuroPride to Riga, hoping “that an event of [that] scale would bring international attention to this issue.” Or that’s how I pitched it anyway. The world needed to know about this politically expedient, historic occasion, and, according to me, I was The Queer for the job.

My present-tense queerness was more jaded than before, though. When I still went out. When I still thought gay bars were utopian spaces filled with magical queer people.

“It was the first time in the city’s history that a rainbow flag had been publicly displayed.”

The last woman I’d really liked had evaporated into thin air after three intense months; when it was all over, I was dazed, bruised and practically hallucinating from the impact of the crash-and-burn. The experience had given me a new angle on gay life: where I used to think lesbian love was the best love, and lesbian people the best people, I was now certain that lesbians were in fact the absolute worst. As intimately, wholeheartedly and quickly as we were capable of giving love, we could also take it away, just as quickly. In other words, we really knew how to hurt each other. I was able to process the relationship by publishing a quietly rageful essay that enumerated the ways Alice Toklas used to torture Gertrude Stein—withhold sex, mess with her transcripts—and nurture her—typing up her notebooks for publishers, providing a constant flow of encouragement and praise. Yup, lesbians were the sickest and the sweetest.

This feeling was made more terrible by the legalization of gay marriage. Suddenly my life was filled with wedding registries, bridal showers, reports of ring shopping—and though I was happy for my friends, another part of me balked (and was jealous). This was not what I had signed up for. As a young queer, I had been guided by desire, and had expected that desire to never end or arrive at an agreed-upon happy ending. As John Waters said, “I always thought the privilege of being gay is that we don’t have to get married or go into the Army.”

When had the embodied excitement of queer desire become stagnated as a problem in my mind? I wasn’t sure exactly. But by the time I got to Riga, it had become obvious that somewhere along the yellow brick road, I had stepped in shit.

On my first day reporting on EuroPride, I arrived with my recorder and my notebook to the headquarters, stationed in a cultural center downtown. In the courtyard, a rainbow flag hung at half-mast; almost immediately, one of the organizers pointed out to me that it was the first time in the city’s history that a rainbow flag had been publicly displayed. Cop cars lined the street out front. Inside, the volunteers registering EuroPriders were young and aloof, saying maybe three words to me between them. I glanced around the bar, notebook in hand, looking needy and pained. Queer standoffishness (an international language apparently) combined with an (actual) language barrier threw me into self-doubt. I wanted to ask people about what this large-scale Pride meant to them; to get to this question, it seemed important that I first gather how they identified: “bi-romantic/homo-sexual,” said a red-haired femme, who was also a volunteer. “I used to sleep with women but am sleeping with men right now;” “gay online, straight at my job.” Lots of awkward pauses, fumbled words, me feeling like an asshole. Was it a discomfort with sexuality that I was hearing? With identity? Or a discomfort with language around sexuality and identity? It took me a while to figure out that a lot of the discomfort I was feeling was my own.

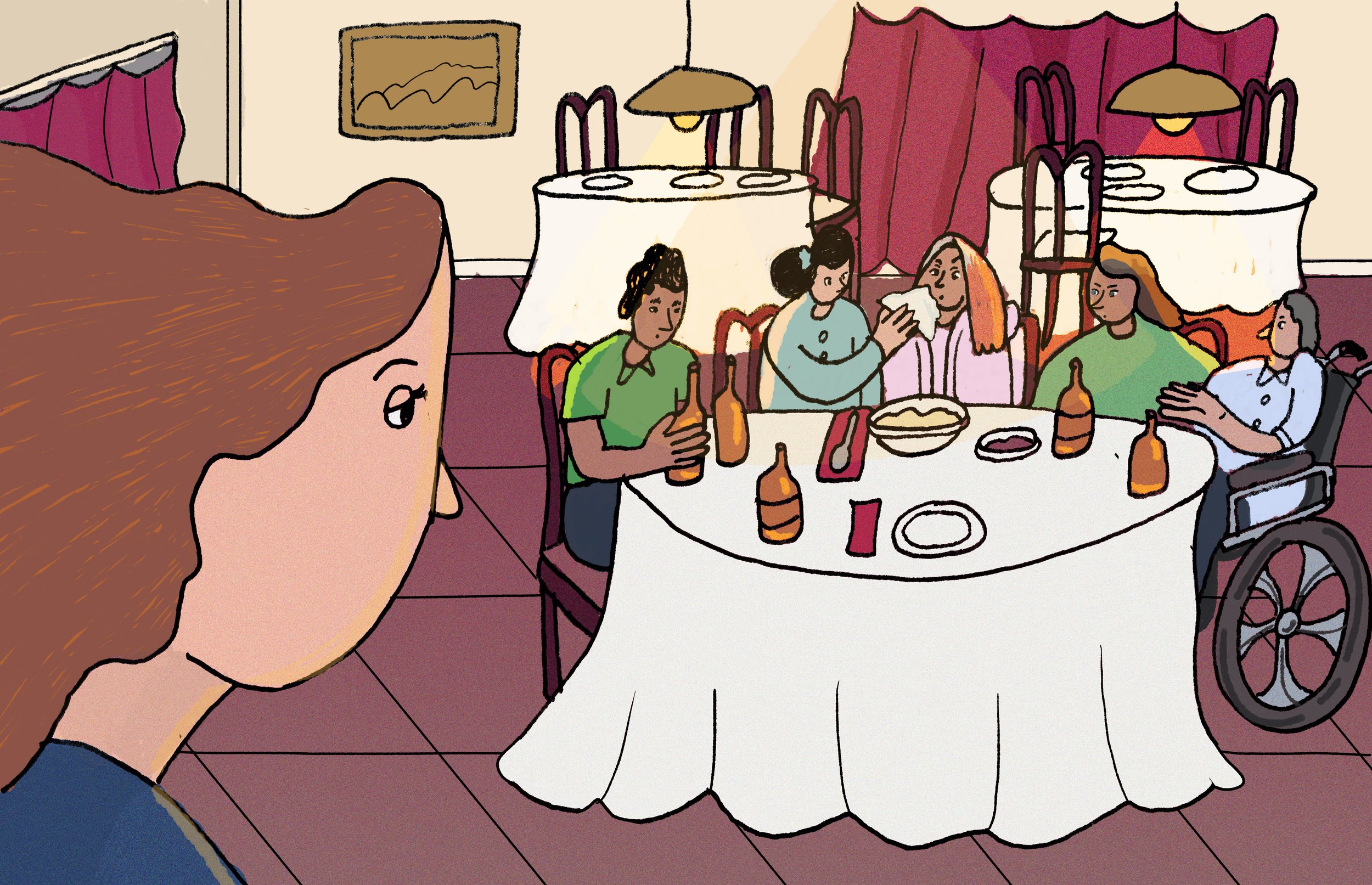

One night I went on a little adventure with the photographer for the story to XXL, a club that had been described to me as the most sordid and the most Russian of the gay clubs in Riga. Outside the bar, a sign with a rainbow and the word "SAUNA" hung above the door. To enter, we had to ring a doorbell labeled "FACE CONTROL.” In the corner of the bar, a muscular male dancer—decked out in a black wig, bustier top, short jean shorts, fishnet stockings, and Toms slip-ons—did an idle sidestep in front of a stripper pole. The owners, a burly masculine couple in their fifties, said we could come in and interview them as long as the photographer didn’t take pictures of the clientele. As we were sitting down to chat, I saw a scuffle near the bar. A tan skinny guy in sunglasses and a cap had shoved the photographer, and was yelling at him in Russian. “I only asked him if I could take his picture!” Joseph said terrified. The owners laughed it off and sat down to talk to me. They told me they had been together for twenty years but both of them still identified as bisexual. “We love the womens,” they said. I couldn’t think of a single gay male friend in the US who would talk about women this way. In fact, many of the queer people I knew back home, myself included, defined their sexuality as rigidly as straight people did.

“He certainly wouldn’t be announcing on Facebook that he was going to EuroPride or anything like that. And why should he? This American idea of putting all your private business online was ludicrous.”

It became clear to me pretty quickly that this Western-made idea of coming out—a forward-moving narrative where one lives a lie, realizes it, abandons former sexuality and is forever free and finished—didn’t quite translate here, like a bad dub of the Wizard of OZ. It also became clear to me that, without realizing it or wanting to particularly, I had adopted that liberation narrative myself. And how nicely did that narrative of static sexuality complement homophobia? 90% of the population was born straight, 10% was born gay, and that was that. Conversation closed and threat averted.

It was meeting a EuroPride volunteer named Gus that helped me shake free from that narrative. Gus was a construction worker in short shorts, an army cap and a thick handlebar moustache—straight out of a gay porno from the 1970s. His favorite magazine was BUTT, he said. He was having sex with guys right now, he said, but resented the question—based as it was on the supposition that his sexual identity was fixed, and that coming out was a natural thing. Of course, no one at work can know, he said. Obviously, everyone affiliated with Mozaika, the one and only LGBT rights organization in Latvia, knew. But he certainly wouldn't be announcing on Facebook that he was going to EuroPride or anything like that. And why should he? This American idea of putting all your private business online was ludicrous.

By the last few days at EuroPride, Gus had sort of attached himself to me, voluntarily becoming my right-hand translator and my little pet. He would find me older gay men to talk to, men with millions of interesting stories about being gay during the Soviet Union, stories that were irrelevant to my task at hand. I talked to them for hours anyway, partly because I wanted to and partly because Gus really wanted me to.

On my last night, Gus walked me home to my Airbnb, which was right next door to the hipster-y Chomsky Bar. He asked me if I wanted to have a drink. When I said no, he loitered at the gates there for a sec, shifting his feet, awkwardly occupying a very pregnant pause. I was pretty slow to recognize what was going on, but suddenly I got it. Gus wanted me to invite him up to my BnB! He liked me and wanted to know me more. I felt like I was going to cry from the sweetness and earnestness of it all. Excited as I was by this mutual moment of openness to each other, a turn of events totally unforeseen, I didn’t invite him up. (I had an early flight and a story to write for God’s sakes!)

Nonetheless, I’d gotten back that queer feeling! That pleasure of surprise and destabilization! The discovery that my sexuality hadn’t ended or arrived at a conclusion. That it could still surprise me and feel special and weird.

Back in the states, I spent the next four weeks writing my story for VICE. I opened my Tinder profile up to men and women, dating some of each and all. Then Trump got elected and I experienced a return to (lesbian) form: I met my life partner, a rescue cat named Aurora, and life, as I knew it, was totally different and exactly the same.

And still, I am eternally grateful to Gus, the EuroPride volunteer and construction worker from Latvia, with the handlebar mustache and short shorts, who loosened me up if only for a second.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Svetlana Kitto is a writer and oral historian in New York City. Her writing has been featured in The Cut, Hyperallergic, Guernica, the New York Times, VICE, Interview, and BOMB, among other publications. Since 2013, she's curated the reading and performance series, Adult Contemporary. She's contributed oral histories to archives and exhibitions at the Brooklyn Historical Society, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Museum of Arts and Design, and NYPL for Performing Arts. In addition to freelance writing and interviewing, she works as a writer and editor for the gallery Gordon Robichaux in NYC.

Header photo by Jordan Sanchez.