Hie in Ho Chi Minh

When Roland Kelts was commissioned by a travel magazine to write about Vietnam, he was drawn to the vestiges of its war with the United States. But he was seduced by a man on a motorbike.

As we landed at Ho Chi Minh airport I saw in thickets at the runway's edge the olive husks of two US military transport vehicles, their front grills twisted awry as if they couldn't bear to face each other. "Like props," I wrote in my notebook. "I've arrived."

The name of the land was meaning enough. Vietnam was a great American novel spun into epic film that swelled like opera and slivered in the mind like poetry. Vietnam happened to America and became another of its storied tragedies, and I was an Asian American who'd read its books, listened to its baleful rock songs and seen the better of its movies. I already knew what it meant: Going After Cacciato, Purple Haze, Apocalypse Now, The Tet Offensive and The Mai Lai Massacre, heroin, hookers and a sad collection of letters home I had read repeatedly called "Dear America."

That first night opened up into a tropical downpour while I walked the side streets around my Lonely Planet hotel with a camera and thick spiral notebook and got wet and lost fast. Men eyed me from beneath canopies, smoking and drinking and, I realized, often laughing at me, a wan foreigner without an umbrella. One of them shouted and I turned away, breaking into a jog. I tried to look like I knew where I was going but I just wanted to find my way back to the lobby.

“He showed me how to slouch into the sunken nook of his vinyl bike seat and drape my arms across his belly and squeeze hard enough not to fall off, but not too hard.”

At a tourist café in the morning a British expat advised me to move to a hotel owned by a Mr. Lai, who ran it more like a bed-and-breakfast. He offered to take me there with my luggage on his motorbike, the mention of which I found coolly English until I realized that 90 percent of the vehicles clogging the city's unpaved streets were motorbikes.

James Salter wrote that there were people we were born to talk to, and like so many of them in my memory, Hie was just there, short, squat and round-faced, a smooth-skinned twenty-something slowing down next to me as I walked. I answered his questions tersely, hoping he'd leave, but he stayed with me, turning the engine off and pushing his bike alongside: You live in Japan, ah. Oh, you're from New York. I want to go there. How can I go there?

At the hotel I asked about Hie. Mr. Lai squinted through the lobby window. "He's okay," he said.

For the next 13 days, Hie took me everywhere he thought I should go. He showed me how to slouch into the sunken nook of his vinyl bike seat and drape my arms across his belly and squeeze hard enough not to fall off, but not too hard. He took me to a smoke shop where an elderly couple at the counter handed me top value in dong for my dollars and yen and a free pack of clove cigarettes. I folded the bills into my right sock and a Ziploc bag I wedged between shirt and belt above my crotch because Hie told me to. "The thief will cut your fanny pack or back pocket with a small sharp knife." I soon trusted everything he said. (As I write this, I don't know why.)

Hie showed me how to cross the streets, none of which had traffic lights or signs. Look straight ahead, like this, he said, eyes comically wide. Don't look at drivers. If they know you see them, they keep going.

On the main thoroughfares we rode inches from other bikes, rickshaws and rusty Toyota pickups, many carrying cages of live chickens or piglets and bushels of cilantro and fruit. We never wore helmets and I paid him in food and beer, asking him to take me to where he usually ate. We sat on plastic seats or overturned buckets in stucco shanties under awnings propped up by tent poles. His friends would smile and comment as Hie introduced me, occasionally translating their remarks: "They say you look half-Vietnamese, your father must be GI," was common. "I tell them, no, he is a Japanese."

It didn't matter that I was half Japanese, born and raised in the US. For Hie, I would be a Japanese.

“When he got back to Vietnam he knew they’d lose the war because none of the US soldiers wanted to be there. They smoked marijuana in their barracks at night, he said, listened to rock music and read letters from home, sobbing aloud.”

Our ride to the Mekong River took four hours because we kept stopping to visit Hie's pals. We had lunch at what I soon realized was a tiny whorehouse; Hie ducked into a back room with a tall middle-aged woman and I was joined near a hammock by a thin girl in a violet ao dai draped over her bare legs. She tried to feed me a spoonful of mango but I gently pushed her hand away, knocked on the back door and told Hie I'd be waiting outside. He joined me a few minutes later and without talking we got back on the road.

Hie introduced me to a boat pilot who called himself Arthur and spoke with a slight baritone twang. He'd spent two years in Texas learning to fly a helicopter, Arthur explained as he rowed us upriver, and when he got back to Vietnam he knew they'd lose the war because none of the US soldiers wanted to be there. They smoked marijuana in their barracks at night, he said, listened to rock music and read letters from home, sobbing aloud.

Back on land, I asked Hie to take me to the War Crimes Museum (formerly the American War Crimes Museum and now The War Remnants Museum) and the Cu Chi tunnels, the elaborate underground network where Viet Cong fighters both hid and launched stealth attacks on the American-allied South. He’d been reluctant, I began to realize, to take me to either one, and after he relented the next day, I had to negotiate for longer stays at both. Twenty minutes, he'd say. No, I'd reply, two hours.

Two hours was maybe too much. On the museum's sunlit walls the war was still happening in pictures of kinetic brutality, black and white and beautifully shot, most taken by American photographers for Life and other US glossies but never published—GIs grinning as they dragged naked POWs through city streets tethered to a jeep's rear bumper, or triumphantly held aloft the chunks of a tattered corpse; swollen faces and twisted limbs disfigured by napalm and Agent Orange; and a typed letter pinned under glass from DuPont Chemical to a redacted name in Washington, D.C., urging the expansion of chemical warfare.

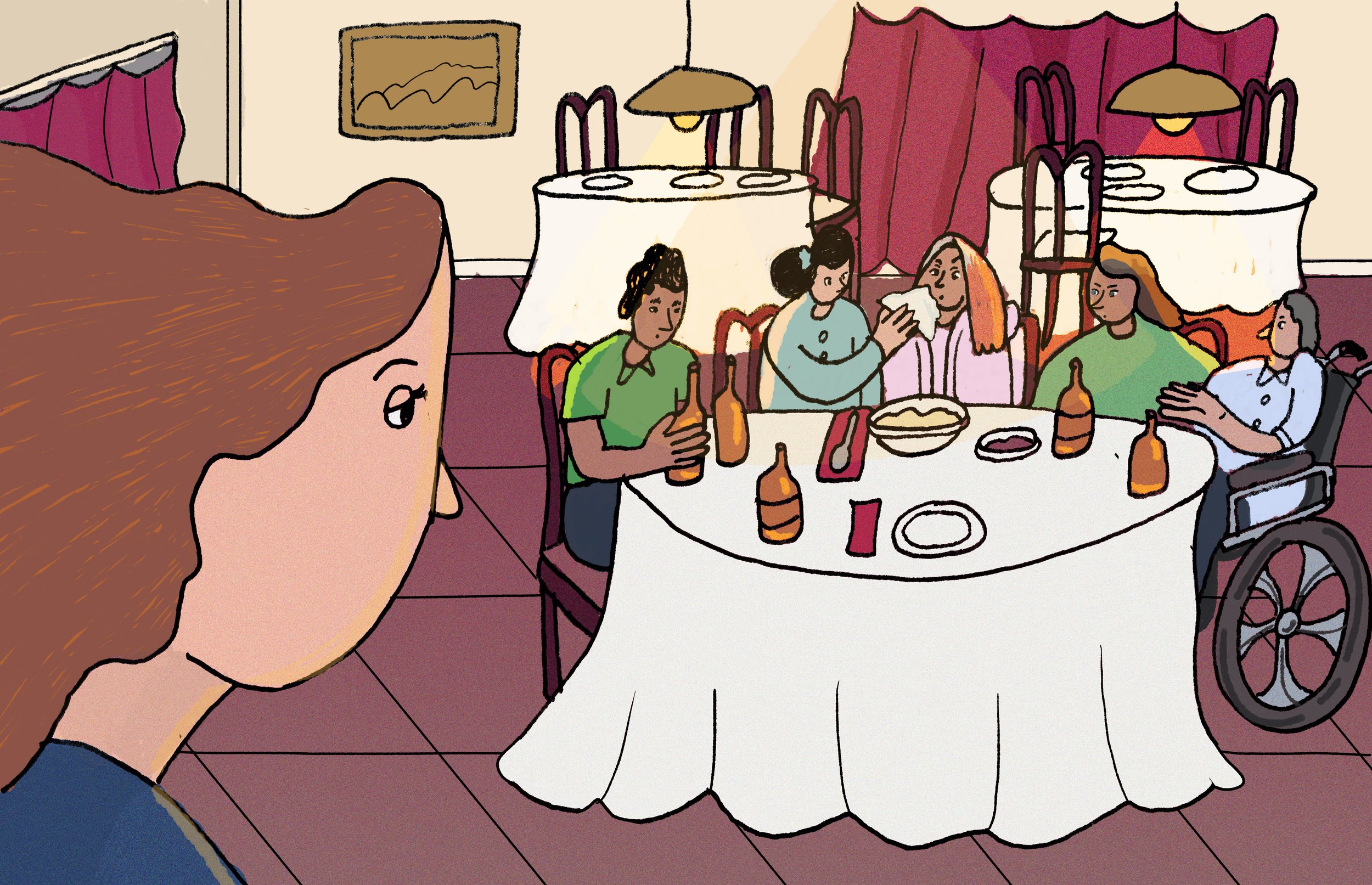

The night before my departure, Hie invited me to dinner at his home. He met me at the hotel with his friend, Hui ("Hwee"), who was skinny and older and flashed a wide tobacco-flecked smile. We drove away from the city past broad rice paddies where the roads narrowed into overgrown pathways. Hui pulled up parallel when space allowed, grinning and winking at me and laughing for no reason. I didn't know where I was or where we were going, and as the streetlights receded, I cared and didn't care in spasms. I laughed back.

We turned into a dark corridor between two rows of shacks and empty lots, wheels wobbling on wooden planks sunk into mud. In Hie's shack we sat cross-legged on the linoleum floor drinking beer from plastic jugs while his wife ladled noodles in a viscous brown sauce into bowls lined with greens. A video played on the television screen behind us. When the ribbons of imagery straightened out I could tell it was a wedding. "That's us," Hie said, pointing to his wife, who blinked and looked down and never spoke.

The two men were asking about my parents when Hie suddenly announced that his father would've liked me but he was dead. What happened? I asked. "He was shot in the war," Hie said, "fighting for the other side. The Americans got him." Before I could reply he raised his jug, and Hui raised his, and they both said "History!" in off-key unison.

Photo by Hiep Nguyen.

Hie insisted he would take me to the airport, and the next morning there he was again, curbside as I stuffed my two duffel bags into the trunk of a small taxi. Mr. Lai had told me that motorbikes were not allowed at the airport, so here’s what Hie did: He rode adjacent to the slow-moving taxi for a few blocks, waved at the driver to pull over, handed him some cash wrapped in tissue paper and collected my bags from the trunk, slinging them both over his shoulders. He pointed to the back of his bike seat and I climbed on.

The roof of the airport was visible above a clump of trees when we were stopped at the security gate. As Hie argued with the uniformed guard, I picked up my bags and handed him a page from my notebook on which I'd written in block letters my postal addresses in Japan and the US, my phone numbers, my email address, and my signature. He grabbed the page and glanced at me briefly, his eyes bulging and streaked red. He was still bickering with the guard when I pressed my hand to his shoulder. "Thank you," I said in English, and walked the rest of the way.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Portrait by Takahashi Nobumasa.

Roland Kelts is the author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US, and he writes for publications in the US, Europe and Japan, such as The New Yorker, The New York Times, Harper's Magazine, The Christian Science Monitor, The Guardian, The New Statesman, Time magazine, The Yomiuri, The Japan Times and others. He is also a frequent media commentator on Japan and Asia for CNN, NPR, NHK and the BBC. Recently, Kelts gave speeches at The World Economic Forum in China and TED Talks in Japan, and he was a 2017 Nieman Fellow in journalism at Harvard University. This summer he will be a guest lecturer at Waseda University, his grandfather’s alma mater. He lives in Tokyo and New York.

Header photo by Lee Aik Soon.