8:45 p.m. at the Selinsgrove Speedway

Listen to this essay on the Atlas Obscura podcast.

8:45 p.m. at the Selinsgrove Speedway is a wall of sound rising up from the sprint cars racing around the half-mile track of clay and dirt. A wall so impenetrable and absolute it feels like nothing could live inside this ceaseless thunder of agitation.

A month ago, my wife and I moved into our house in the old part of downtown Selinsgrove, a small borough along the banks of the Susquehanna River in central Pennsylvania. We are newcomers to the area, though our American foursquare with the sagging front porch is older than the 1946 speedway standing on the southern edge of town. I have heard the cars from a distance. I have smelled the burning gasoline and clutches and rubber. I have listened to the sound of roaring engines, the distant turbulence equal parts familiar and indecipherable from the comfort of my bed a mile and a half away. But it’s only on the last race of the season, in late August, that my neighbor invites me out to the track and I finally see the speedway from within.

The grandstand tickets are cheaper, but he says that we’ll end up coated in a layer of dirt from the cars that lean too hard on the outside turns of the track. The pit, he insists, is really where you want to be.

The pit lies on the inside of the track, forming an oval island of grass and muddy earth. In the beginning, I feel like I am marooned there, the cars circling on all sides in a continuous loop, one sustained fortissimo coda of oil and horsepower and steel. When my neighbor says something to me, when his mouth makes the shapes that would generally produce something like words, all I can hear are the engines. I nod. I gesture. I say nothing.

When the sun is halfway gone and the sky is burnished by smoke and fumes, the halogen lights kick on, illuminating the track in a haze of yellow. A crush of mayflies swarm the artificial glow in such numbers that the tumult of their bodies dancing through the light looks like a flurry of snow that never reaches the ground and instead remains suspended in disarray. The birds follow the mayflies, which in turndisappear back into the birds. Whole life cycles unfurl and end there in the vortex of raucous quietude.

When the cars exit the track, my sense of the world returns slowly. There is a buzzing in my chest, cotton in my ears. I ask my neighbor if the races are over and my voice doesn’t even sound like it comes from me. No, he says, those were just the time trials. The racing hasn’t even begun yet.

Without the cars, there is a lull, and in that lull, a host of new sounds make themselves known. There’s a chorus of crickets. The plaintive cries of killdeer fill the air as they forage the grass for food. From inside the track, the singing of the national anthem is tinny and obscure, the words themselves an afterthought to the countless small dramas unfolding within the pit.

When the racing starts up again, cars come flying around the turn with reckless precision, passing so close that I instinctively shuffle back. It is strange to imagine that there are people behind each wheel—that beneath the tremendous roar of engines, the rush of blood and the beating of so many wild hearts is what sings the night alive.

About the Author

Matt Jones is a writer living in the Susquehanna River Valley. His writing has appeared in The Southern Review, New England Review, Threepenny Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, and various other publications. More of his work can be found online at mattjonesfiction.com.

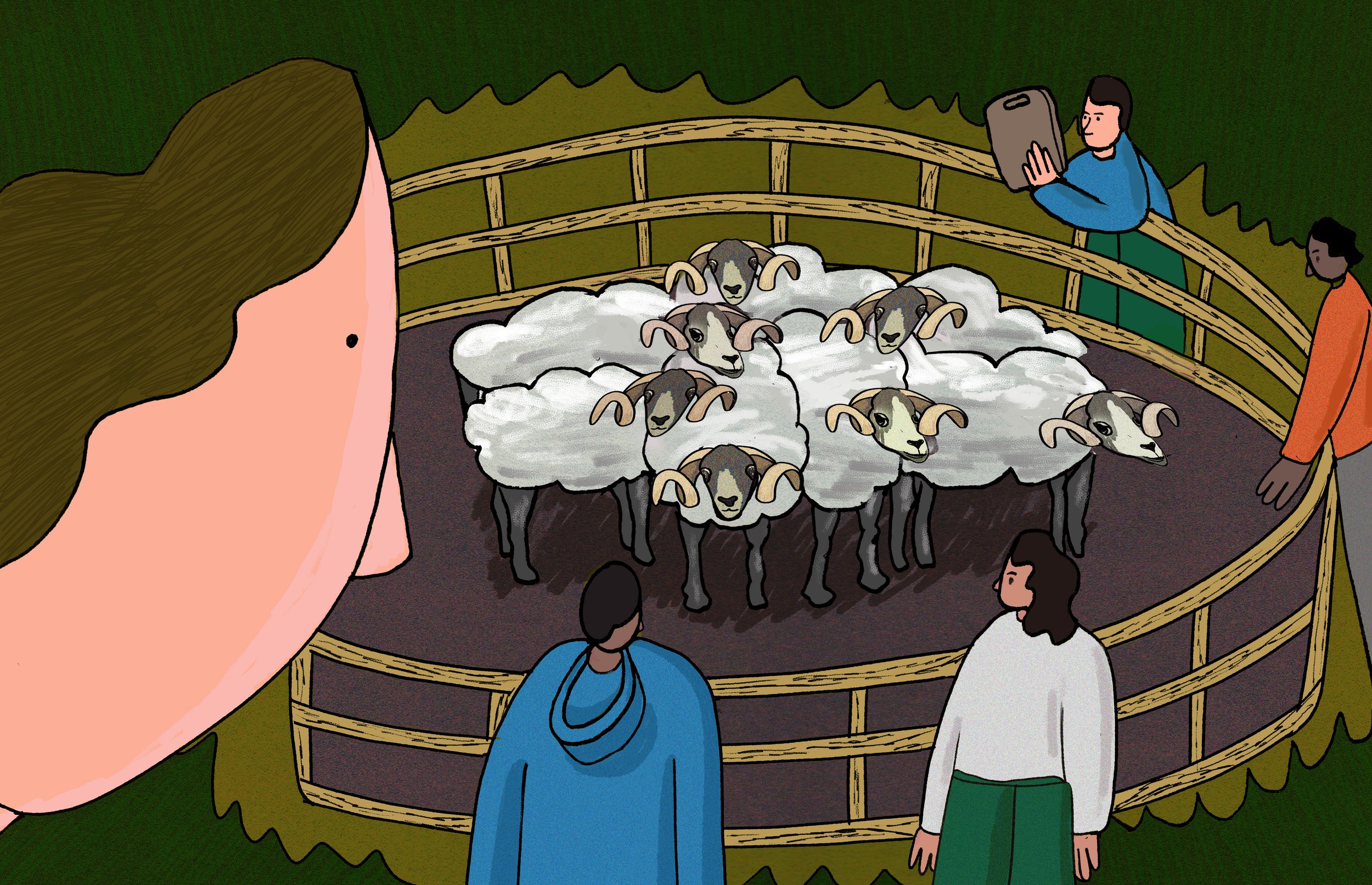

Illustration by Jane Demarest.

Edited by Aube Rey Lescure.