Into the Gray

Every trip we take unfolds a myriad stories all at once, and after we get back home, we tell only a few of them, even to ourselves. When I traveled to Iceland in 1987, to write a short piece for Time magazine about midsummer madness and a place that still speaks a medieval language, I knew that my obligation was to record the curiosities of white nights and a summer without dark for readers who could barely imagine them; the main thing I had to keep out of my story was myself.

“Anyone who writes about his travels knows that it’s these other stories that stay with us, largely because they’re untold, even as they form us in some covert way, making up the secret story of our lives.”

But under the surface of the strictly factual little piece of reportage I brought back, all hard facts and sharp edges, I was always aware of a far deeper story, more haunting and forever unresolved, that was for me what truly gave the trip meaning and makes it live inside me still. Anyone who writes about his travels knows that it’s these other stories that stay with us, largely because they’re untold, even as they form us in some covert way, making up the secret story of our lives. Paul Theroux explored this wonderfully in his shadow-series of fictional autobiographies, including My Secret History and My Other Life, tantalizing readers with the sense that he was giving us the intimate stories behind the stories in his books. I tend to hold these stories inside myself, where they keep playing out, unstoppably, and come to resonate more powerfully precisely because they’re never voiced.

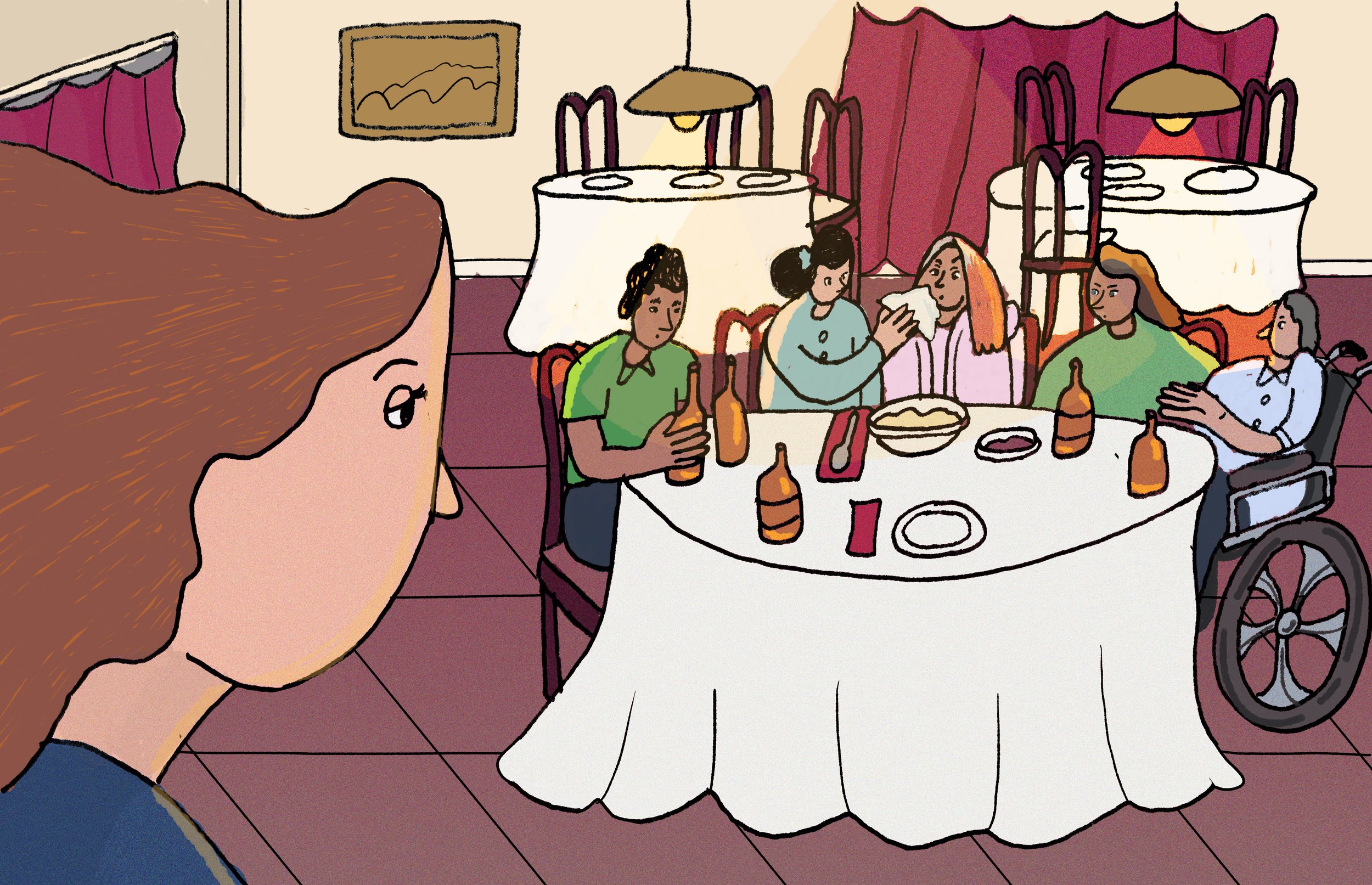

My first day in Reykjavik, a girl at a table in the corner of a small café began staring at me and staring at me, transfixed. Icelandic gazes have a particular intensity, I’d learned, as if arising from all the empty space across the island, its vast, wind-haunted, treeless wastes. Iceland also has more unworldly beauties per capita than any nation on earth. For a single traveler, this can lead to a powerful kind of dream-state: Everyone looks like a bronze-skinned goddess, and the visitor is an exotic because he’s not (and in my case had black hair and brown skin besides).

The girl at the table in the corner looked at me and looked at me and I didn’t know how to respond. Was this one of the island’s many eccentric customs? Was it a register of my Otherness in an island so remote that most people looked very much like their neighbors? (Was it because I was the rare soul not eating pan-fried puffin?) Whatever the reason, the girl at the table finally got up, left her female friend behind, and asked me what I was reading.

“Ah, Graham Greene,” she said, noting my copy of Our Man in Havana. “I love him.”

She sat down, and very soon it was past midnight, and we were entering a parallel world.

The café closed its doors and we walked out into the ash-gray streets and walked and walked without direction. We talked and talked about all the places we hadn’t been till now. We went dancing for a while in the disco named after John Lennon and she stared at me so intently I felt it underneath my shirt. I told her about Cuba, Lhasa, Kyoto, all the places I’d just been that seemed like magic worlds, faraway Icelands, to her. She had a slow way of saying yes and eyes with an Egyptian slant to them. Their blue as shockingly clear as the sea when first glimpsed around mountain turns.

We walked and walked, through silent, ghosted streets, and sat beside a river in the dove-gray light. We passed down long straight lanes that could have led to her room or to mine. She turned back towards her home, and I went back to the small bare cell where I was staying, and wrote ice-blue poems until the dawn. Except that dawn is never-ending in the long Icelandic summer.

Through all of this—and this is why I remember it so fiercely (her eyes staring as she danced, her cheeks suddenly flushed, the way she twirled herself about in the street at 1 a.m. and then stood still for a photo, “so you’ll always remember that girl in Iceland”)—we didn’t do much more than probe and try to fathom the nature of the Other. I was a foreigner to her, with my talk of white-sand beaches and red-robed monks in the high lamaseries of the Himalayas; she—like everything around her—was a lunar interval to me. Travel is always an erogenous zone because you’re far from home, and nobody knows who you are or who you’re meant to be: Anything can happen. The part of you that thinks of résumés and appointments is stilled; the part that hungers for surrender is wide awake.

“Sex?” W. H. Auden had asked in his Letters from Iceland. “Uninhibited.” But nowhere is it more uninhibited than in the imagination. And so we walked and walked, she telling me about her studies in African dance, I telling her about places where it was dark in summer, and the days had shape. We met the next day, and the next; each night we walked into the gray and my week in Iceland began to become the story of everything we were not saying and all the many things we were not quite doing (she had a boyfriend somewhere in the town, and I was on my way from Cuba to Japan).

“Longing lasts far longer than repletion, and all the things one hasn’t done possess one far more than all the things one has.”

Had the girl from Iceland and I met on more familiar ground, I might have tried to place her in some way—to make her real, or push us towards some kind of resolution. Had we chosen to step out of the streets, into my room, I might have had a gift-wrapped experience that would be as dead to me now as all the other mementos I brought back from the island of few trees. But somehow we had the sense to keep the door wide open and everything a little out of reach. Longing lasts far longer than repletion, and all the things one hasn’t done possess one far more than all the things one has.

When I came home, I gave my editors just the kind of 900 words they had expected, even as I tossed and turned in my bed, plotting how to return. Four years on, I got another magazine to send me back, and I came out with a 6,000-word essay on the island. But everything that’s important in that essay is between the lines: The reader walks through a quirky place where there are no dogs in the capital, where there’s no beer, and where there’s no television on Thursdays; I see the penetrating gaze of a dark-haired girl with blue Egyptian eyes, even though I met her only briefly (and with her husband) on that return trip.

I think of the girl in Iceland more, I suspect, than I think of many of the people I came to know much better. I think of the long steep streets and the chill pearl light; the fork in the road sometime before dawn (and her stepping into a public phone-booth to tell her mother she wouldn’t be coming home that night). I hear our footsteps echoing down the empty paths, catch the scuffling of a paper bag whipped along in the wind at 3 a.m. I see her face flush as I call her name when she comes around a corner.

The stories you never quite tell possess you even as the ones you share lie unbreathing on a shelf.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Pico Iyer has presented talks for TED.com on both movement and stillness and is the author of eight books on the travel shelves, including, most recently, The Man Within My Head. Though a seasoned traveler, Iyer felt completely out his element at the Albertville Winter Olympics, covering the luge. He was responsible for writing about every winter sport. His only credential? Hating all winter sports.

Header photo by Julius Jansen