To the Logari Who Asked About the Sun

I apologize if I seemed cold. It was just that I was afraid. You see, since the moment I arrived in Logar that summer of 2012, when I was 19, my uncles had been telling me to be wary of locals. No one could know I was back home because word spread so quickly in our little village. In fact, my eldest uncle Ahmadzia Maamaa—may Allah have mercy on his soul—very explicitly warned me not to tell anyone my father’s name or that I had come from America. He escorted me about the countryside, wherever I went, to make sure I was safe. “I promised your father no harm would come to you here,” he told me. “What harm?” I said, laughing, though I had an idea.

The tide was shifting then. Government forces were losing control. Militias set up checkpoints in the markets during the day, but the Taliban ran the roads at night. More than anything, though, my uncles were afraid of bandits. “A bandit,” Ahmadzia Maamaa explained to me, “can be a Talib or a policeman or a militiaman or a shepherd or a shopkeeper or anybody at all.”

This is all just to say that I had been explicitly ordered not to speak with someone like you—a stranger, a Logari, a “potential bandit”—on the day you approached me in the field behind my grandfather’s compound. Ahmadzia Maamaa would have made me come inside with him, but the cows needed watching while they grazed, and Ahmadzia Maamaa had urgent business in Wagh Jan, which was why I was alone, tending to cows in an empty field, when you came strolling up to me.

I have to admit, Kaakaa: you looked so much like a Talib, with your big black beard and your woolen shawl and your black pakol. I half expected you to be hiding an AK beneath your pattu. Staring at the clay beneath my feet, I prayed you would pass by without a word, but you stopped and said Salaam.

We exchanged greetings in Pashto, and I tried not to let my accent slip, not to reveal myself as a foreigner. I could tell you sensed something was wrong; what looked like suspicion—or curiosity—washed over your face. You asked me for my father’s name. That was when a minor war played out inside of me. Not a war. A skirmish. A firefight. My first instinct was to lie. Just make up a name on the spot. A phantom father. Someone you couldn’t recognize or condemn. Perhaps I could say that Ahmadzia Maamaa was my father. Claim I was my cousin. How would you know? But I’ve never been a good liar, or, honestly, a quick thinker. Besides, my father is my father. He destroyed his body to raise me up. How could I deny him then?

“I’m Dawa Jan’s son,” I said.

“Dawa Jan?” you said, “Hajji Alo’s son?”

“That’s the one,” I said.

You smiled and told me that my father was once your classmate, that you had been friends decades ago, before the war(s). “Your father was a real palawan,” you said. “Everyone was afraid of him.”

“I’m still afraid of him,” I said.

And you laughed, truly, from your belly, so that I was finally sure I was with a friend.

“It was as we were basking in the fading light of the countryside that you asked me if there was a sun in America.”

We talked for a bit about my family, your family, my life in America, your life in Logar. The sun was just beginning to set behind the black mountains in the distance, and before us all the rolling fields and the lonesome trees were taking on an incredible purplish hue, and it was as we were basking in the fading light of the countryside that you asked me if there was a sun in America.

“Pa Amerika ke mar sta?” you said.

I thought I misheard you. I apologized and asked you to repeat yourself.

“Pa Amerika ke mar sta?” you repeated.

You have to understand, Kaakaa, Pashto was the language I had grown up speaking, the language through which I had first learned to curse and joke and love. It was the language I had lost, bit by bit, in learning English, and it was precisely in these moments, when my understanding of my own language failed me, that I felt the falsest, and the least worthy of my father’s name.

But you were so patient with me. You repeated yourself a third time, watched me shake my head, and went on to explain that your daughter had recently immigrated to London with her husband, and that she called you every night and complained that it was so foggy and dreary in London, it was as if the sun never rose. You said that she desperately missed the sunlight in Logar, and so you were wondering if it was the same in America, if the sun rose there.

I smiled, finally understanding, and explained that California was very sunny, very beautiful, but that nothing could compare to a Logari sunset, and you agreed, of course, and we stood there together in the evidence of Logar’s splendor, just before darkness fell.

I returned to the States a few weeks later and wandered about California in a daze. I missed Logar so much. During my classes at Sac State, I would start daydreaming about the mountains and the trails and the mulberries and the wheat, and sometimes, when stuck in traffic on a hot day, a cold breeze would hit me square in the face with a scent of woodsmoke and barley that would transport me back to Logar. Even now, Kaakaa, I often think of our conversation in that field behind my grandfather’s compound. I think about me and you and your daughter as well. I imagine her walking the foggy roads of London, through mist or rainfall, with only the memory of sunlight carrying her forward.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

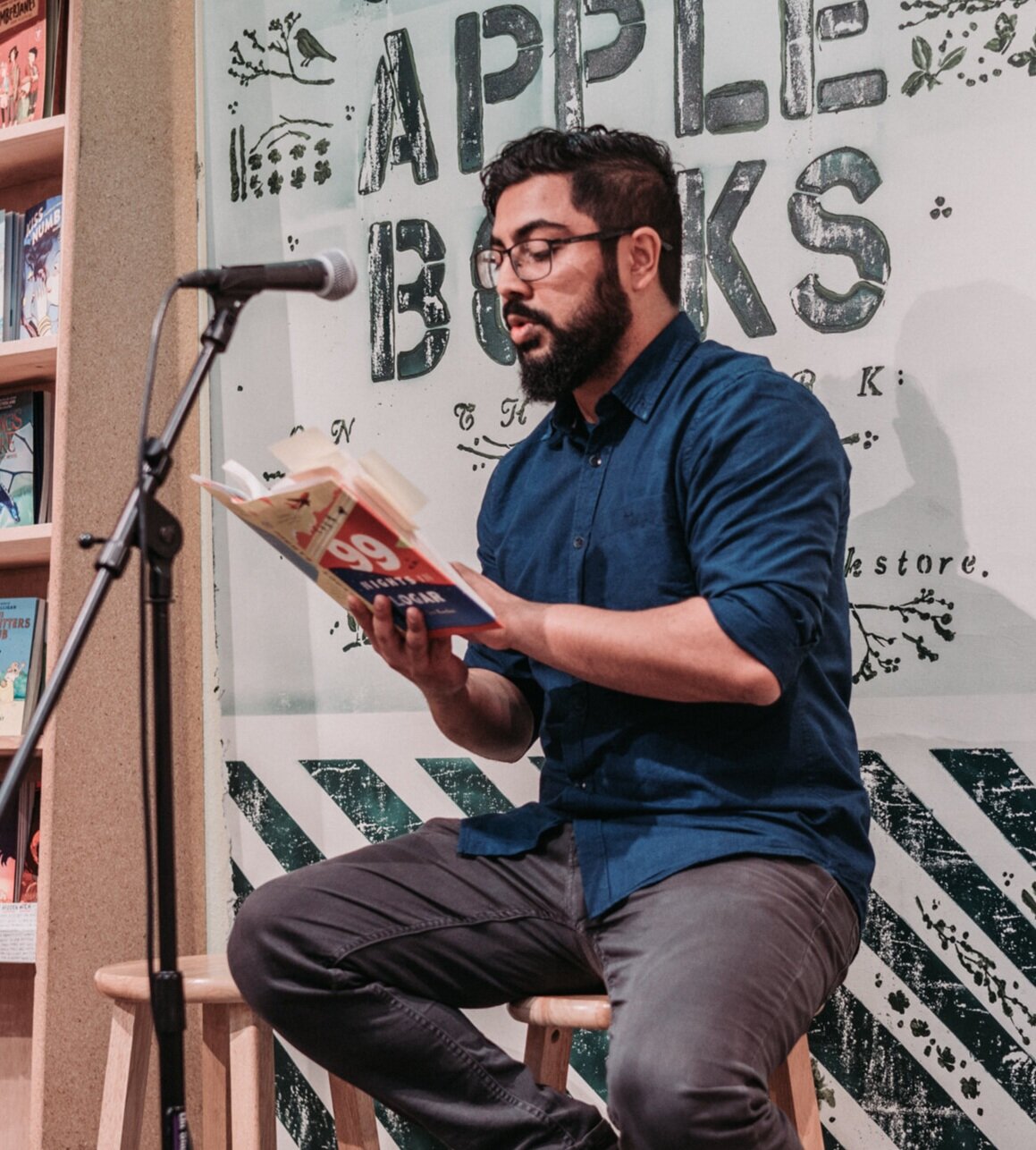

Jamil Jan Kochai is the author of 99 Nights in Logar (Viking, 2019), a finalist for the Pen/Hemingway Award for Debut Novel and the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. He was born in an Afghan refugee camp in Peshawar, Pakistan, but he originally hails from Logar, Afghanistan. His short stories and essays have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Ploughshares, and The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018. Currently, he is a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University.

Read Jamil’s “Behind the Essay” interview in our newsletter.

Header photo by Adam Dillon